We may earn income from links in this post. Please read this Disclosure for details.

As whitecaps splash across the bow of our boat, I clutch the railing and peer through the spray hoping to glimpse my first sighting of Grosse Île through the mist.

While many passengers on this day cruise are headed to the island to sightsee, hike or pay their respects to the Irish Memorial, I’m retracing the steps of my great-grandmother.

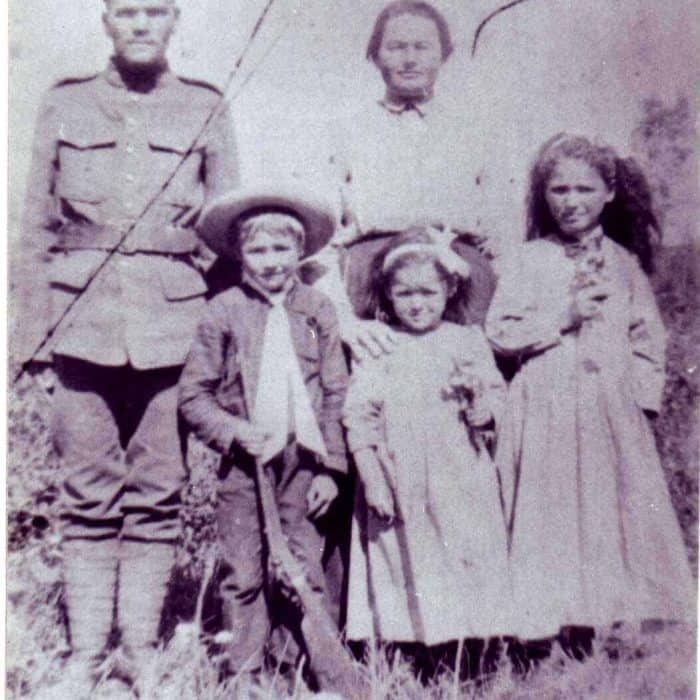

She spent almost a month here with her four young children (including my grandmother) in 1913 when this isolated island in the middle of the St. Lawrence River served as a quarantine station for the Port of Québec City.

Lured by the promise of free, fertile farmland, my ancestors were part of a wave of immigrants who came to Canada between 1868 and 1914 when the western provinces opened for settlement.

Why is Grosse Île Important?

In the mid-19th century, the Port of Québec City was the first port of entry to Canada for immigrants from many countries including Ireland, Ukraine, Poland, France and Italy.

Following a cholera epidemic that swept through Québec in 1831, all immigrants were examined for illness prior to disembarkation.

After inspection by immigration doctors, healthy passengers would travel onward to their destinations in Canada.

From 1832-1937, more than four million immigrants passed through this quarantine station on Grosse Île.

Ill passengers were treated at the island’s hospital or–as many Irish immigrants who arrived during the tragic events of 1847–were buried here.

Researching Family Roots in Ukraine

My personal pilgrimage to this windswept island actually began several years earlier when I travelled to Ukraine. I traced the maternal side of our family ancestry to the small village of Kapustyntsi east of Kyiv.

Founded officially in 482 AD, the capital city of Kyiv is positioned on the banks of Dnieper River, the dividing line between east and west Ukraine.

For me–the first in my immediate family to step foot in Ukraine since our ancestors left–the sight of the mighty waterway from the city’s hills was exhilarating.

Most impressive was the sight of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra (also known as Kyiv Monastery of the Caves). It rises from a forest of spectacular horse-chestnut trees on a plateau overlooking the Dnieper River.

Set within fortified walls, this ancient complex of monastic buildings, museums and churches was founded by St. Anthony and St. Theodosius in 1051.

Next, we walked to the National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art, home to more than 80,000 pieces of traditional folk art dating from the 15th century.

The hand-drawn ceramics, decorative Petrykivka painting of homes and household items, pysanky (egg decoration), weaving and wood carving are all important parts of traditional Ukrainian culture and identity.

Of special interest to me was the embroidery. The patterns and colours hold symbolic meanings drawn from pagan roots, Slavic mythology and Christianity.

My mother remembers her own Ukrainian vyshyvanka (traditional blouse) embroidered in a motif of red flowers wrapped in vines, representing purity and immortal beauty.

Like many Ukrainian immigrants, my ancestors were farmers. To get a sense of rural life as it may have been in the late 1800s, I headed to the Pirogovo open-air museum on the outskirts of Kyiv.

This living Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine features buildings dating to the 16th century.

It includes a domed wooden church, windmills for grinding grain, a school and peasant homes set on peaceful fields surrounded by forest.

Stepping into the thatched-roof homes was like stepping back in time.

Many of the techniques Ukrainians used to build the sod houses were replicated when settling Canada’s west.

Ukrainian Immigration to Canada

Back in Canada, I hoped to learn more about where my ancestors first set foot on Canadian soil.

I turned online to the pros at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax for help.

In addition to the museum’s historic artifacts, the Scotiabank Family History Centre offers remote research services.

Located on the Halifax waterfront, it’s the ideal place to learn about the immigration experience.

It’s also a popular attraction for visitors taking a New England Cruise from Boston to Quebec City or Montreal.

The museum presents 400 years of immigration history in Canada in an evocative way. It’s filled with stories of personal journeys and exhibits, including advertising campaigns promoting Canada as the “New Homeland” during the peak of Canadian Settlement between 1896 and 1914.

🌟 Pro Tip: You can also search Ship Passenger Lists (1865-1922) online at Library and Archives Canada.

Immigration records showed that my great-grandfather arrived in Canada in October 1912.

My great-grandmother and children aged 4, 3, 2 and 1 followed, travelling by train and ship across Europe to Southampton, England.

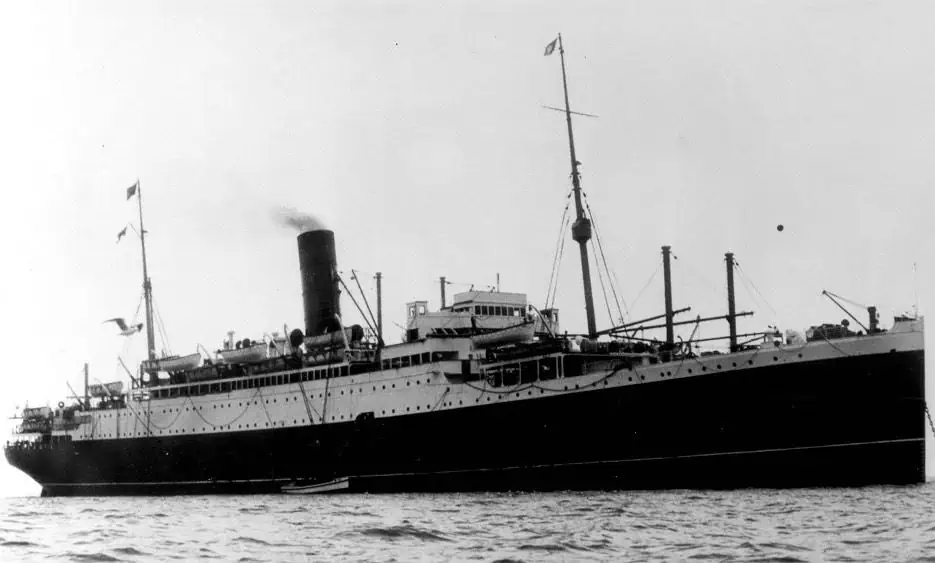

From there they journeyed across the Atlantic on the SS Ausonia. It was a 7,907 ton ocean liner with accommodation for 37 1st class and 1,000 3rd class passengers.

Built in 1909 and originally named the Tortona, it was sold to the Cunard Line and sailed a route from Southhampton to Quebec City and Montreal in the St. Lawrence River.

I can only imagine the challenges she faced travelling alone with such young children in an era with rudimentary comforts.

According to hospital records, the challenges didn’t end for my great-grandmother upon arrival in Canada in August 1913.

All four children were diagnosed with diphtheria and measles and transferred to the Hospital Sector on Grosse Île in the St. Lawrence River.

There, they spent nearly a month in quarantine.

Grosse Île History and Modern Day Status

Now, I’m arriving on Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site of Canada at the same time of year almost 110 years later.

Designated a National Historic Site in 1974, Grosse Île played an important role in Canadian history.

The quarantine station and hospital which operated from 1832 to 1937 were established to combat the spread of deadly infectious diseases, in particular cholera.

Located 46 kilometres downstream from Quebec City, it’s one of 21 islands in the Isle-aux-Grues archipelago.

Today, Grosse Ile and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site is administered by Parks Canada and is open to the public seasonally.

Because it’s accessible only by boat or plane, most people visit as I am, on a day trip from the village of Berthier-sur-Mer on the south shore of the St. Lawrence (Google Map).

The tour company Croisières Lachance offers a narrated round-trip cruise to the island.

Once on the island passengers are met by Parks Canada guides who share the history of the 2.7 km long island on an escorted tour.

Parks Canada Guided Tours at Grosse Île

During my visit, the sun breaks through the clouds as we approach Grosse Île. Wave action from two tides a day have carved deep into its bedrock to create steep cliffs and rocky shores topped by shrubby red cedar, oak and maple.

We disembark from the ship, as most immigrants would have, at the western wharf where we’re met by a Parks Canada guide who escorts us first to the Disinfection Building.

This wooden building erected in 1892 was where passengers and their personal belongings were disinfected upon arrival.

The facility was part of a modernization program (that included microbiology, epidemiology, disinfection and vaccination) introduced by Dr. Frederick Montizambert, who was the station’s medical director from 1869 to 1899.

Passengers would have been examined for signs of infectious disease by a station doctor. They would have placed their clothing and belongings inside quarantine bags for disinfection.

Then they would have proceeded to the shower area.

While the long rows of metal shower stalls appear grim by today’s standards, during its time it was intended to be comfortable with warm running water and electricity.

Following a disinfection shower, passengers would have been transferred to the first, second and third class hotels on the island to wait out their quarantine.

Earlier immigrants, especially the Irish arriving in 1847 after the Great Potato Famine, weren’t so fortunate.

The Irish Tragedy of 1847-1848

More than 5,000 Irish immigrants died in the ocean crossing, suffering from typhus and malnutrition. Others arrived in such a weakened state they died awaiting disembarkation and on Grosse Île itself.

During our tour we walk to the western sector of the island. Here, the rows of white crosses of the Irish cemetery line a grassy knoll.

An estimated 5,424 people died on Grosse Île in 1847-1848. At the peak of the Irish tragedy, the dead were buried in mass graves.

An evocative memorial created by artist Lucienne Cornet records the names of the Irish, other immigrants and medical staff who lost their lives in that deadly period.

Rows of Brennans, Briens, McCarthys and McDonalds name entire families wiped out by typhus and other illnesses.

At the western promontory we come to the stone Celtic Cross, erected in 1909. It soars into the sky, honouring the memory of the Irish who perished.

Memories of the Past

A shuttle bus then takes us to the eastern point of the island, passing ominous-sounding Cholera Bay and Hospital Bay.

🌟 Pro Tip: Watch for unique flora and fauna along the way. Grosse Île’s plant life numbers 600 species, 21 of them considered rare in Québec!

We arrive at the Village Sector, home to several well-restored wood-framed buildings including the doctor’s house, school and nurses residence.

The Village Sector’s isolated location was intended to protect station staff from infectious disease by segregation.

The Hospital Sector is located at the island’s furthermost point. It’s where ill passengers, such as my grandmother and her siblings, were treated.

Originally patients were housed in tents and then hastily constructed shelters in an open field.

By 1913, permanent hospital quarters provided well-ventilated lodging.

Patients were transported by a horse-drawn ambulance from the eastern wharf to the hospital where nurses cared for patients.

I stand in the treatment room where almost certainly my grandmother and her siblings convalesced.

It’s an eerie place.

In 1913, medical professionals believed sunlight was harmful to patients with smallpox. So all the windows and lightbulbs were painted red.

My great-grandmother, who wasn’t ill, would have stayed in separate living quarters near the Village Sector.

I imagine her visiting the Catholic chapel which still stands overlooking the desolate waters of the St. Lawrence.

What did she think of as she waited for her children’s recovery?

What did she think of the St. Lawrence and her first look at Canada?

Life in Canada after Quarantine

My ancestors were fortunate to eventually leave the island. They continued their journey by land across Canada to be united with my great-grandfather.

But their hardships continued.

The farmland they received in Saskatchewan was poor and the youngest child, baby Olga, didn’t survive the harsh prairie winters.

By 1916, during World War 1, my great-grandfather had enlisted in the 44th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, arriving in France in January 1917.

He would be dead less than six months later, his name memorialized on the Vimy Ridge Monument.

No trace of his body was ever found.

After visiting the Canadian National Vimy Memorial near Arras, France, I wrote about his role in the battle of La Coulotte, the epicentre of heavy fighting, in One Man’s Sacrifice.

According to Commonwealth tradition, soldiers were buried where they fell. More than 7,000 are buried in 30 cemeteries within a 16-kilometre radius of the Vimy Memorial.

Some, like my great-grandfather, have no grave stone at all. For those 11,285 soldiers, the Vimy Monument serves as a memorial and focus for contemplation.

Final Thoughts on Grosse Île, Québec

Although my great-grandfather was killed when he was just 36, his family was able to survive on the death benefits.

My grandmother (and surviving siblings) grew to adulthood, had families and created lives such as the one I enjoy today.

As I left Grosse Île, I reflected that it is more than a historic site.

It’s a living memorial to the individual stories of hope, fortitude and hardship of Canada’s immigrants, one that continues to this day.

Plan a Day Trip to Grosse Île from Québec City

Québec City Tourism

Plan your stay, get maps and more at the official Québec City Tourism Website.

Croisières Lachance

Cruises to Grosse Île operate from May 10 to October 8, 2023 with two daily departures.

Croisières Lachance cruise ships depart from the marina at Berthier-sur-Mer (Google Map), a 45 minute drive east of Québec City. Give yourself an hour to find the marina and park. Croisières Lachance

To get to the marina, travel south over the Pierre-Laporte bridge and take Highway 20 East toward Rivière-du-Loup. Take Exit 364 towards Berthier-sur-Mer.

The scenic cruise to Grosse Île takes about 45 minutes. The cruise fare includes admission to the Parks Canada site. 1-418-259-2140 Toll free: 1-888-476-7734

Book tickets online in advance.

🌟 Pro Tip: Pre-order a picnic lunch as there are no restaurant facilities on Grosse Île.

Where to Stay in Quebec City

The Fairmont Le Chateau Frontenac is a world-renowned landmark hotel in Québec City. It features resort amenities including a fitness centre, swimming pool and outdoor terrace. The guest rooms are exceptionally well-appointed.

Many offer signature views of the city or the St. Lawrence. A sumptuous breakfast features locally-sourced ingredients such as Québec artisanal cheeses and honey harvested from its own beehives.

Pro Tip: You can even take a guided tour of the Fairmont Le Chateau Frontenac!

The one-hour tours, led by a local guide interpreting a historical character, begin on Dufferin Terrace. You’ll then head inside Le Chateau Frontenac following in the footsteps of dignitaries who’ve stayed here through the years.

Located in the heart of Old Québec, it’s also conveniently situated for a day trip to Grosse Île. There’s easy access to the Pierre Laporte Bridge and rental cars as well as valet parking.

Check for the best car rental rates at Discovercars.com

Parks Canada

Plan your trip at the official Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site of Canada. The Parks Canada entrance fee is included in the transportation cost.

Thank you to Destination Québec cite, Parks Canada, the Canadian Immigration Museum at Pier 21, JC Travel (Ukraine), my mother Nydia Peterson and my sister Lesley Peterson for their help and support in researching this story.

Other Eastern Canada Travel Ideas

FAQs

The Parks Canada site of Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site can be visited seasonally by boat or by plane. The admission fee is included in the transportation cost.

The island of Grosse Île is one of 20 islands that form the Archipel de L’Isle-aux-Grues, in the St. Lawrence River’s Middle Estuary in Quebec, Canada. It’s accessible by Croisières Lachance boat or by plane.

Many people visit Grosse Île to learn about the role of the quarantine station in Canada’s immigration history and to pay their respects at the Irish Memorial National Historic Site. Others come to enjoy the island’s windswept beauty and hike its scenic paths such as the Mirador Trail and Lovers Trail.

Dividing her time between Canada, Guatemala and Mexico (or the nearest tropical beach), Michele Peterson is the founder of A Taste for Travel. Her award-winning travel and food writing has appeared in Lonely Planet’s cookbook Mexico: From the Source, National Geographic Traveler, Fodor’s and 100+ other publications.

Read more about Michele Peterson.

Easy Mezcal Paloma (Mezcal Grapefruit Cocktail)

Easy Mezcal Paloma (Mezcal Grapefruit Cocktail)

Marlene Cashin

What a fantastic story and research!

Michele Peterson

Thanks so much Marlene! I had a lot of help on the research!